How The Gambia is Modernizing Education Data: Insights from the 2nd KIX Knowledge Café on Education Data Systems

The Gambia is transforming its education data system with live dashboards, student-level tracking, and community engagement—offering a model for EMIS reform across Africa.

At the 2nd KIX Knowledge Café on Education Data Systems, The Gambia shared an experience with relevance well beyond its borders: how a small nation is rethinking the way education data is collected, shared, and put to use. The shift has been bold yet practical, moving from static PDF yearbooks to live dashboards, from national-level summaries to individual student records, and from top-down reporting to stronger community involvement.

At the heart of this change is the Ministry of Basic and Secondary Education’s (MoBSE) Education Data Centre, which serves as a model for other countries across the continent working to modernize their education management information systems (EMIS).

From Annual Census to Dynamic Dashboards

Until recently, education data in The Gambia followed a familiar rhythm. Each November, schools filled out the paper-based annual census forms, which were then checked and processed over several months. By May, the results appeared in a thick statistical yearbook. While yearbooks provided valuable benchmarks, they often arrived too late. Schools had already changed, teachers had been reassigned, and enrollment patterns had shifted.

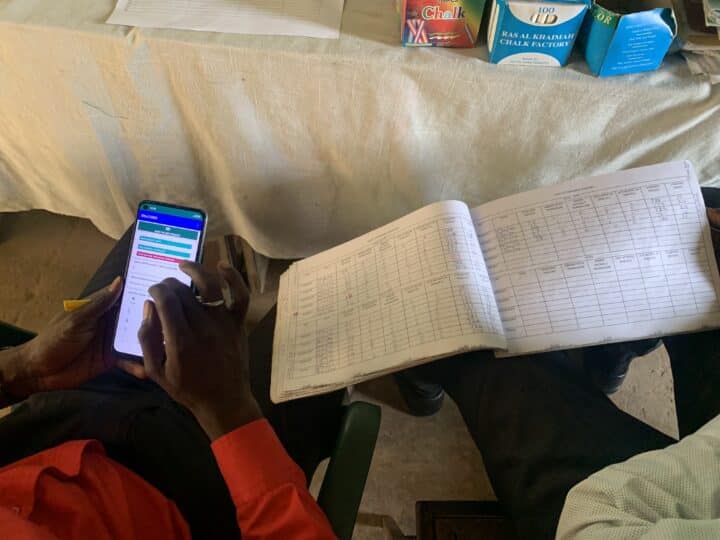

With the move to DHIS2-Ed—an education-specific version of the open-source platform first built for health information—the way that education data is managed has been shaken up. Instead of waiting months for a comprehensive yearbook, policymakers, regional officers, and even school leaders can now log in to live dashboards on MoBSE’s Education Data Centre (EDC), which updates as new information flows in.

Historical census data has been migrated into the centre, which has created an interactive archive for trend analysis. New modules on daily attendance and exam results feed near real-time insights directly into the EDC.

The Gambian team’s message at the Knowledge Café was simple but powerful: data is no longer just a tool for reporting upwards. It is becoming a more accessible resource for planning, problem-solving, and accountability across every level of the education system.

From Aggregate to Individual-Level Tracking

One of the most significant shifts in The Gambia’s education reforms has been the move toward individual student data. In the past, EMIS focused on school-level figures: total enrollment with breakdowns by gender, classrooms, and teachers. While useful, this masked key details, such as which children and youth were dropping out of education or how poverty and location affected learning.

Starting with pilot efforts in 2020, MoBSE launched a digital student registry. Each learner received a unique ID, and schools slowly but surely began recording information on socio-economic background, attendance, and progression. The pilot, tested with Chromebooks in 200 schools, has since scaled nationwide. Today, nearly 80% of Gambian learners are included.

This step-by-step rollout has made all the difference. By adding individual-level data to the traditional aggregates, The Gambia can now track issues like dropout hotspots, regional disparities, and the impacts of specific interventions. With tools such as the DHIS2-Ed School-based EMIS (SEMIS), schools themselves are not just supplying data into a one-way, upward pipeline, but increasingly being encouraged to put it to use.

School Report Cards and Community Engagement

The Gambia’s reforms are bringing data closer to communities. The School Report Card (SRC), delivered through dashboards, presents school performance in clear, accessible visuals that parents, teachers, and School Management Committees can easily interpret.

Rather than waiting for annual meetings or wading through lengthy reports, communities can now see up-to-date information on resources, attendance, and learning outcomes. This shift brings about not only transparency, but agency. Parents can ask why attendance rates are slipping, committees can push for additional teachers, and local leaders can mobilize support based on data and evidence that they trust.

Equity is not just a matter of top-down policy. It also depends on action “from below,” where communities use data to push for fairness and quality. The School Report Card offers a practical way of turning that principle into practice.

Why This Matters for Africa’s EMIS Reform Agenda

The Gambia’s experience comes at a moment when many African countries are rethinking how they manage education data. Across the continent, systems still depend on centralized, paper-based cycles that are slow to produce results and often hide the inequalities that stand in the way of progress toward SDG4 and the Continental Education Strategy for Africa (CESA).

By showing how an open-source platform like DHIS2 can be used for education data, The Gambia offers a practical model for EMIS reform. The health sector has already demonstrated how open-source platforms can handle large-scale, decentralized data. Now education is beginning to follow the same path, with The Gambia being a pioneer to take this forward. Its example provides a practical and forward-looking model for others across Africa and beyond.

What makes this case especially relevant is the focus on institutionalization. The reforms go beyond the tech. They are about building ownership at regional levels, training staff, and weaving new practices into everyday school routines. Partnerships with the University of The Gambia, HISP West and Central Africa, and international partners have created a support network that links technical innovation with long-term capacity building.

Key Takeaways for Other Countries

The Gambian delegation closed their Knowledge Café session with reflections that resonate beyond borders:

- Start simple, then build: Digitizing existing yearbooks into dashboards was an easy win that demonstrated the power of the system, building momentum for change

- Pilot, learn, scale: The learner registry began as a small pilot, giving space to test and adapt before expanding to cover nearly the entire country

- Keep equity at the center: By collecting individual-level data, governments gain a clearer picture of who is left behind and can act to close the gap

- Invest in people, not just technology: Regional trainings, workshops, and university partnerships are building the skills and leadership needed to sustain the system over time

- Engage communities: Tools like the School Report Card show that data isn’t just for policy makers, but can be a bridge between schools and society.

The Gambia’s story is not just about building an Education Data Centre. It is about the journey of reshaping the relationship between data and decision-making. By moving from static reports to dynamic dashboards, from aggregates to individual tracking, and from closed offices to open community engagement, the country is showing what an equity-sensitive EMIS can look like in Africa.

For countries across the continent grappling with similar challenges, The Gambia offers a simple but powerful lesson: data reforms are not just about technology. They are about fairness, accountability, and giving every child a chance to be seen.

Relevant resources: https://www.iped.africa/news-event/au-iped-hosts-knowledge-cafe-to-deepen-peer-learning-on-responsive-education-data-systems